Using trees and environmental science as a backdrop, forest ecologist finds synergy with those excluded from science—and society.

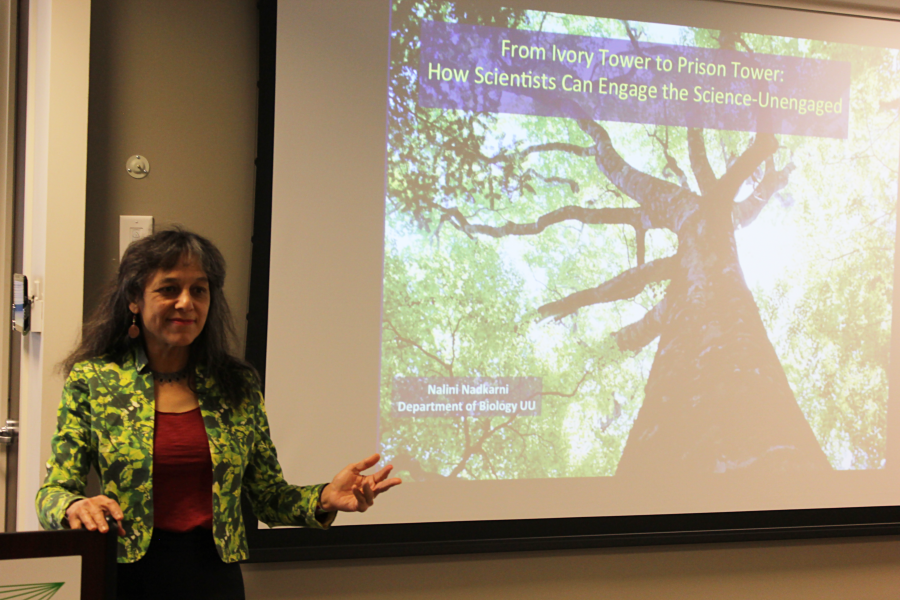

A tree moves more than you think. So do the minds of people in correctional institutions. In her SESYNC Seminar, Dr. Nalini Nadkarni discussed the ecological role of tree canopy rainforest plants, connecting trees and humans, and how she has linked the ecological value of trees with existing values of groups not typically engaged with science.

Nadkarni, professor of biology at University of Utah and a leader in public engagement with ecology, has opened minds to science in the most unexpected places: prisons. It’s where she brings science and environment lectures to inmates, leads conservation projects that grow prairie plants and raise endangered Oregon spotted frogs for wetlands, and brings nature imagery to confined environments. In these programs, she challenges conventional thinking of stagnant entities by moving perspectives on what is possible while providing links to environmental science.

In her research in forest ecology Nadkarni has studies epiphytes, plants that grow in in the tree canopy, and how these plants recover from disturbance. Among other things, she has found that recovering from disturbance takes far longer than one would expect. For example, when you scrape away moss from a tree branch, the tree takes over 20 years to grow the same vegetation.

She also dispels the idea that trees are fixed in place. She said, “They are moving constantly if you look at the movement in the canopy.” To measure precisely, Nadkarni tied paintbrushes onto the twigs of a maple tree and held up a canvas to capture the movement over two minutes. Then, she measured the segments and found that the collective distance of the tree twigs measured 186,780 miles—or about seven times around the Earth.

By tapping into the same notion that we presume inmates in a fixed position, Nadkarni sought to break that concept by establishing connections to basic science, grow minds, build conservation programs that include inmates, and connect ecological value of trees with social justice. “I felt one of the worst things about incarcerated barrier to access to nature,” she said.

Nadkarni is known as the “queen of canopy research” for her discoveries in the tops of trees in tropical systems. She could equally be called the queen of science communication, for her ability to bring science to non-scientists, through aesthetics, fashion design, prisons, religion, and even Barbie dolls. She has run programs on science with urban youth and religious groups, and brings botanically correct fabrics to fashion designers. Through the STEM Ambassador program, she trains other scientists to become representatives by developing their skills to link the scientific community to other parts of society.

Today, human activities threaten Nadkarni’s research in Costa Rica’s Monte Verde. She recalled hearing the piercing sound of a chainsaw in the distance, but the real disturbance she is thinking about is climate change. “Cloud forests are one of the most vulnerable ecosystems. The dry season Monte Verde is getting longer and longer. Canopy is experiencing more drought,” she said. By interweaving the thread of conservation and the ecological value of trees with consumerist ideas, spirituality, and the social justice, she is trying to bring science and nature to people who might not automatically think trees are important.