Study Finds Ebola Virus Outbreaks Connected with Deforestation

In December 2013, a 2-year-old boy from a village close to Gueckedou, in southern Guinea, fell ill with a mysterious illness characterized by a fever, vomiting, and black stool. He died two days later. This was the first human case of the Ebola virus disease in West Africa for the 2014 outbreak, the World Health Organization later reported.

How the 2-year-old contracted Ebola is still unclear to scientists, but new research supported by the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) provides evidence that outbreaks of the virus were connected with forest fragmentation.

The study was led by Professor Maria Cristina Rulli at the Politecnico di Milano, and was published on February 14 in Scientific Reports.

“We found that Ebola virus disease outbreaks had occurred in areas that were hotspots of deforestation," Dr. David Hayman an author of the study, told the New Zealand Herald.

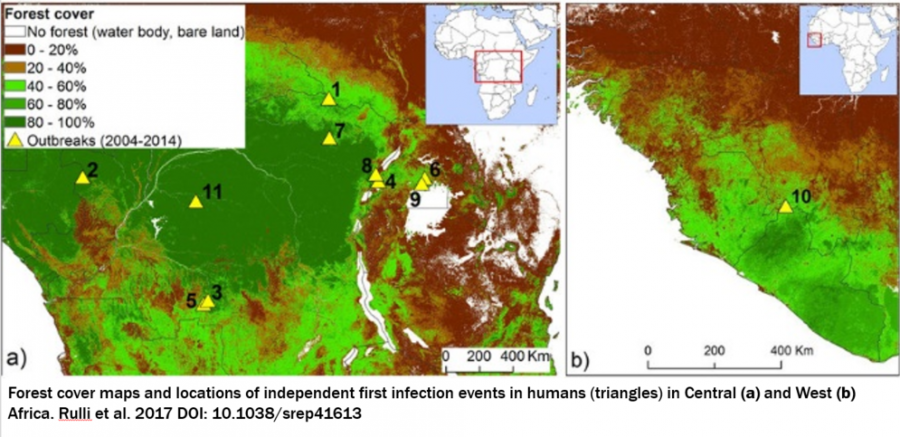

Rulli and colleagues used high-resolution satellite data of forest cover in Central and Western Africa. When overlayed with the eleven locations of first reported cases of Ebola, the researchers found these outbreaks were more likely to occur in locations with fragmented forest cover from deforestation between 2000 and the year of infection.

Professor Paolo D’Odorico, a co-author of the paper who is now at the University of California, Berkeley, started this research as a Sabbatical fellow at SESYNC.

“Our study shows that Ebola virus outbreaks tend to occur in areas with above average forest cover and population density, and that are hotspots of forest fragmentation. We interpret this effect as the result of increased probability of contact between humans and wildlife reservoir species in highly fragmented forest margins. This research provides a quantitative assessment of the possible nexus between land use change and disease outbreaks,” said D’Odorico.

The researchers hypothesize that fruit bats native to the region might be able to grow in numbers in recently deforested patches of forests. These bats are potentially important “disease reservoirs,” meaning they’re not affected by the virus themselves but they spread it to different species, including humans. People living close to recently fragmented forest areas may be increasing their risk of disease exposure.

Environmental scientists typically evaluate the impact of forest and habitat loss in terms of losses of biodiversity, carbon stocks, and changes to water and nutrient cycling. This study highlights how deforestation can potentially impact disease outbreaks and global human health.

The research paper was published in Scientific Reports on February 14. DOI: 10.1038/srep41613

Media Relations Contact:

Emily Cassidy, ecassidy@sesync.org

(410) 919-4990

About SESYNC

SESYNC's mission is to support synthetic, actionable team science on the structure, functioning and sustainability of socio-environmental systems. The center’s five core objectives are to: enhance the effectiveness of interdisciplinary collaborations among natural and social science research teams focused on environmental problems; build capacity and new communities of socio-environmental researchers; provide education programs to enhance interdisciplinarity and understanding of socio-environmental synthesis; enhance computational capacity to promote socio-environmental synthesis; and enhance relevance of socio-environmental research to decisions and behaviors via actionable scholarship. For more information on SESYNC and its activities, please visit www.sesync.org.

Creative Commons image from UN Photo/Martine Perret.