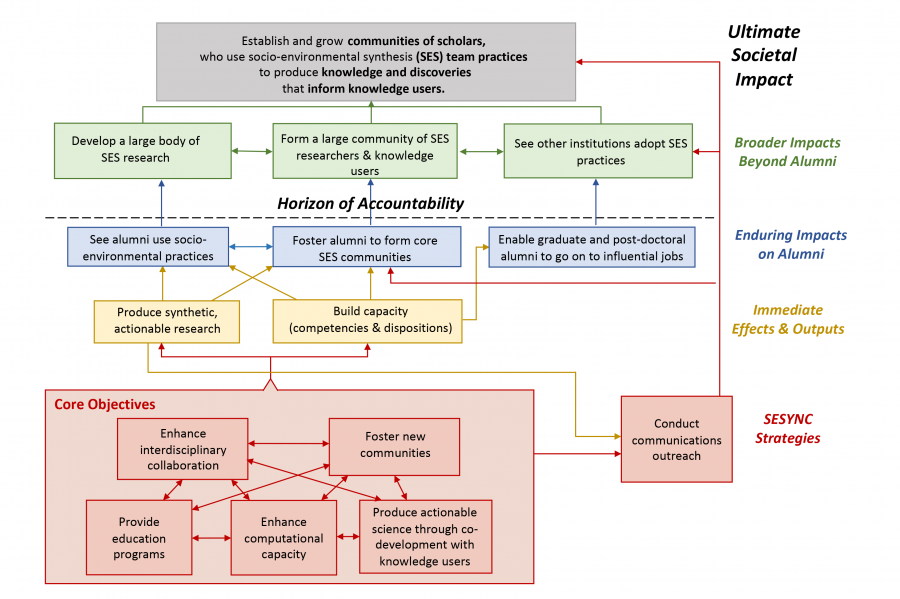

SESYNC’s organizational practices, its programs and activities, and the logic behind them were the result of the center design process reflected in SESYNC’s “Theory of Change” (TOC) (Figure 1). The Center’s 2010 founding leadership—Margaret Palmer, Jonathan Kramer, Jim Boyd, Joan Nassauer, and Bill Fagan—envisioned SESYNC as an adaptive organization. Many things influenced the initial design, including scholarship from the organizational sciences, the science of team science, interdisciplinary studies, and advice from past and ongoing National Science Foundation (NSF) synthesis center leaders. At the time of our proposal, there were certainly notable scholars and even some pioneering groups (e.g., Stockholm Resilience Centre) working in this arena; however, a center did not exist that was designed to serve the broad external research community internationally in growing and building capacity for team-based actionable, socio-environmental research.

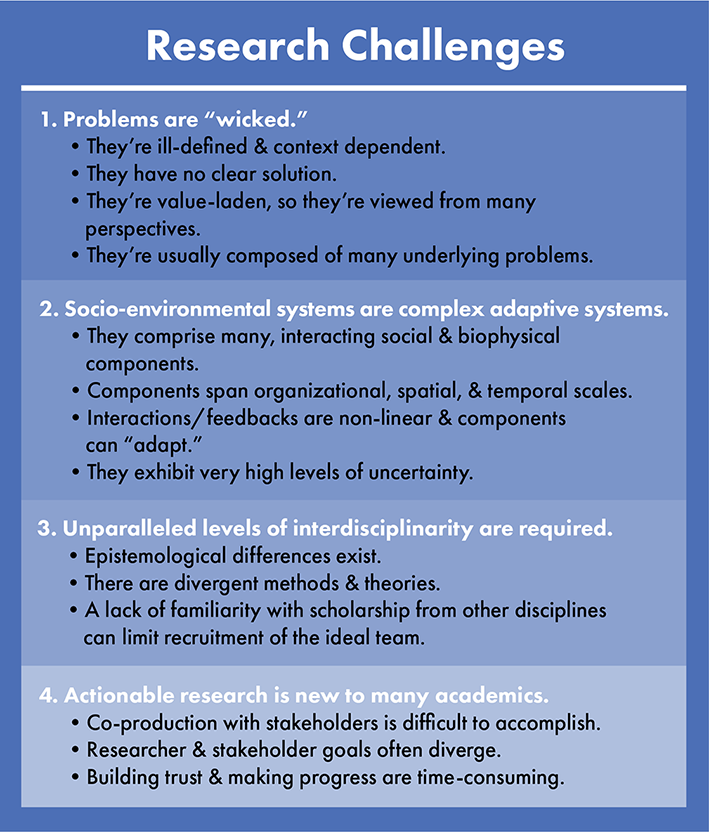

We began the design process by identifying the many challenges that we would likely face. These challenges fell into four broad categories (Figure 2):

- All socio-environmental problems are so-called “wicked” problems—meaning they are value-laden such that one person’s solution may be viewed by another as creating a problem.

- Socio-environmental systems are examples of “complex adaptive systems”—meaning their components and processes exist at, interact across, and change at differing spatial and temporal scales.

- Studying socio-environmental systems or problems requires deeply integrative work by teams of highly interdisciplinary scholars.

- Actionable research—which seeks to identify solution paths or options (and resulting consequences) that have the potential to inform behaviors, decisions, or policies—requires skills that many academic researchers have not developed. These skills require people to think about problems in a different way and to develop comfort in engaging with those who are the decision makers or who are part of organizations advocating for change in the research process.

inform its core objectives (red boxes, Figure 1) and move toward

enduring impacts (blue boxes, Figure 1).

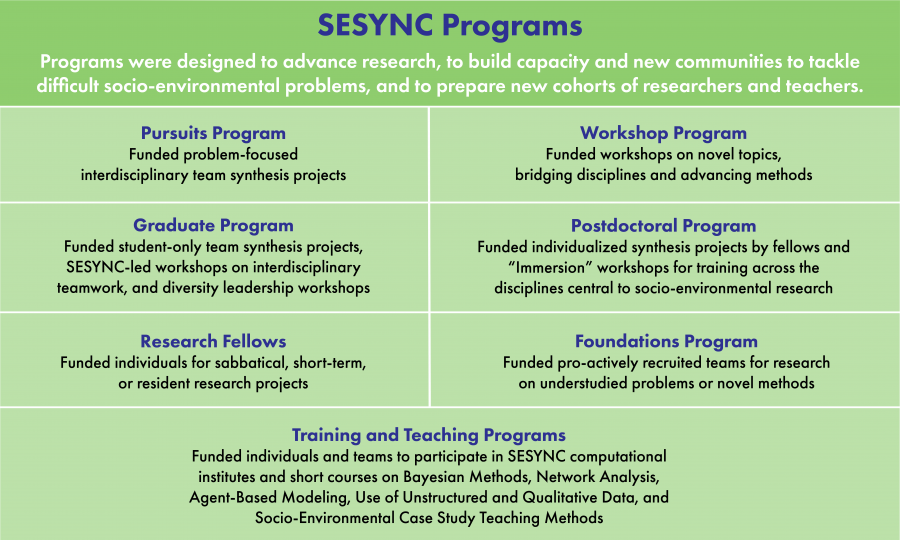

Linking Strategies to Goals: Programs

Considering these many challenges, SESYNC posited that we must go beyond funding and hosting research teams and strive to build capacity and new communities. We wanted to teach scholars to cultivate the competencies and dispositions to work across disciplines and sectors. Thus, we developed programs (Figure 3) to meet the training and education needs that were central to growing capacity to tackle socio-environmental problems. We also created programs that would help scholars meet the computational challenges associated with synthesizing research across methodologically diverse fields and highly heterogeneous types of data. A multi-pronged Postdoctoral program supported original research (through 2-year fellowships) and socio-environmental training workshops (the “Immersion Program”). Experimental programs such as the “Data to Motivate Synthesis" program involved trying new approaches to promote novel research questions and teams by early-career scholars from diverse fields. Short courses, summer institutes, and team-based or one-on-one training extended computational support beyond just the provision of cyberinfrastructure.

Near the end of SESYNC’s second year, we launched a graduate program for training and supporting team synthesis projects by upper-level graduate students. All these programs intended to bolster the competencies and dispositions that integrative socio-environmental research demands, including the skills to bridge epistemologies, integrate diverse methods and data sources, and cope with divergent values and priorities. We hoped that these programs would not only build understanding of socio-environmental systems and research but also help promote solution-driven research and grow the number and types of researchers engaged in socio-environmental research.

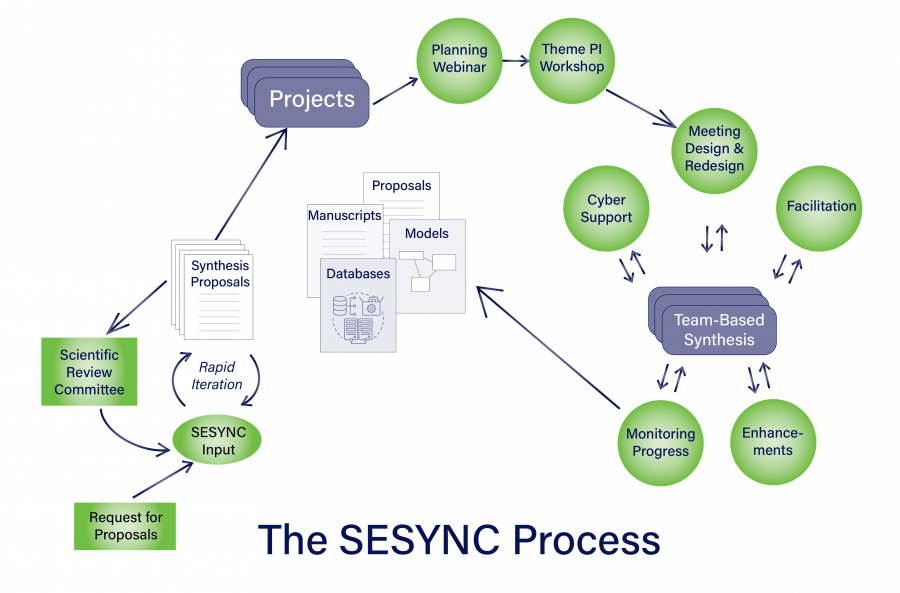

Linking Strategies to Goals: Process

To meet SESYNC’s immediate goals, while moving toward more enduring impacts, we realized that many of the above challenges required more than programmatic and training opportunities for researchers. We posited that deeper engagement and new types of support services would accelerate individual and team progress. Thus, SESYNC staff set out to engage with researchers while they developed project ideas, as they identified team members, and throughout the life cycle of their project. We provided this support in a variety of ways—from highly formal and structured interactions to very informal and even behind-the-scenes efforts to assist researchers. A summary of these interactions are what we came to call the “SESYNC process” (Figure 4), which comprises a set of linked policies, modes of engagement to researchers, and ways to provide flexible support.

(Fully explained in text.)

Rapid Iteration: Collaborative Project Development

Given our mission to build capacity in S-E research, SESYNC staff offered to discuss proposal ideas with team leads prior to submission and provide feedback on optimal revisions following expert review. A highly interactive panel review process facilitated by SESYNC leadership not only sought to identify the strongest proposals but to explore how projects might improve by sharpening questions or considering new methods, clarifying conceptual frameworks, expanding or changing team composition (expertise, disciplinary diversity, and degree of prior collaboration), or considering additional data. Teams received feedback, following the review process, and they then had the chance to respond rapidly (~ a month) and move toward approval to initiate their work.

Planning of Project

All team leads participated in a “priming” webinar with a core set of SESYNC staff that focused exclusively on their project. This discussion gave all a better understanding of the scholarly problem and further introduced the PIs to the resources at the center. We posed a set of standard queries, examining issues regarding data (access, amounts, quantitative or qualitative nature), logistics, potential epistemological hurdles associated with interdisciplinarity, and actionability. We emphasized the central role of leaders in articulating an early vision and in building effective team process.

Team Leads Workshop

Some of the principal investigators (PIs) from SESYNC projects funded in the same period came together for two days of interactive work. They shared their research framework and early project management approaches as well as data and proposed methods. They discussed team composition and focused on the challenges of managing a transdisciplinary research effort. The workshop provided an opportunity for teams to discover joint interests, potentially form new collaborations, and engage in an explicit discussion of team dynamics.

Meetings Design

For many teams, advice on effective meeting structure is very useful. Discussions with SESYNC staff often focused on pre-meeting activities and specific goal-oriented agendas that balance group work with time for individual reflection and opportunities for flexibility.

Facilitation

SESYNC offered meeting facilitation to all teams. In most cases, facilitation required a significant interaction between the facilitator and the team leads. The SESYNC facilitator would become knowledgeable of the problem and language specific to the scholarship prior to the first meeting and then tailored the facilitation process to specific team needs and preferences. Facilitation, particularly in projects’ early phases, often focused on the development of a shared conceptual framework and intended to enhance the involvement of all team members and the sharing of diverse perspectives. Only about 25% of the team leads requested facilitation and due to staffing capacity, SESYNC was only able to provide this service for about 20% of its teams.

Computational and Cyber Support

SESYNC gave each team a comprehensive overview of the computational, analytical, and communication support tools available to them. A dedicated eight-member team of IT and computational experts was available to help before or during team meetings. These experts worked to understand each project’s unique needs and sometimes assisted as participants, combining and analyzing diverse types of data. Ongoing engagement between these staff and team members was a key component of SESYNC’s support structure and extended at least a year beyond the life of the project.

Check-In Meetings and Project Enhancements

Staff and leadership utilized both informal and formal opportunities to gather information from teams and to offer them additional assistance. Casual conversations and shared lunches with teams in residence, as well as structured webinars that engaged multiple teams, revealed both progress and ongoing or emergent challenges. In many cases, leadership and staff used this information to provide additional support (e.g., funding a new team member from a different discipline or providing computational support, training for a team member, or additional facilitation). These interactions also provided opportunities to link teams with potentially shared interests and to invite new project proposals.