In Cuba, 500 years of socio-environmental data sit decaying in the island’s long-neglected church archives. The archives are difficult to access, but contain rich primary sources of data—not just on the transatlantic slave trade and the emergent identities of Cuban society, populations, births, baptisms, marriages, deaths, and burials—but also on original land grants and territorial divisions; transatlantic agricultural and livestock transfers and their New World adaptations; livelihoods; landraces; and extractive industries. In short, key socio-environmental themes that remain largely unexamined in the Cuban context. Although a few provisional descriptions of these repositories have emerged over the years, most of their content remains unknown. The obscurity of these archives and their advanced state of decay are the product of several socio-environmental factors.

First, the United States has had only limited academic engagement with the island over the last half century. Academic visas were difficult to obtain, and the Cuban government did not approve many research proposals. If approved, state interference often burdened research. Red tape stretched from the airport to the archives. The main repository in Havana was difficult to work with, and only a handful of Cuban researchers with limited resources had ventured outside of the capital to identify or consult primary sources. Amidst a general climate of mistrust, access was often denied for both domestic and international researchers, with the exact reasons not always made clear. Planning a research trip was risky and difficult to coordinate without Internet access. Partly as a result of these factors, the socio-environmental history of Cuba has received far less attention than in other Caribbean or Latin American contexts. This represents a significant gap in our understanding of the origins of today’s socio-environmental systems in the Circum-Caribbean and beyond.

Second, the steward of these data sources—the Catholic Church—has had strained relationships with the Cuban government, having been an institutional competitor since 1959. Many churches were, in effect, under lock and key. With plummeting memberships and resource bases their archival record was often neglected. Tomes of data were crammed away and forgotten in wooden cabinets to marinate in the tropical heat, without the funding for or access to modern methods of preservation.

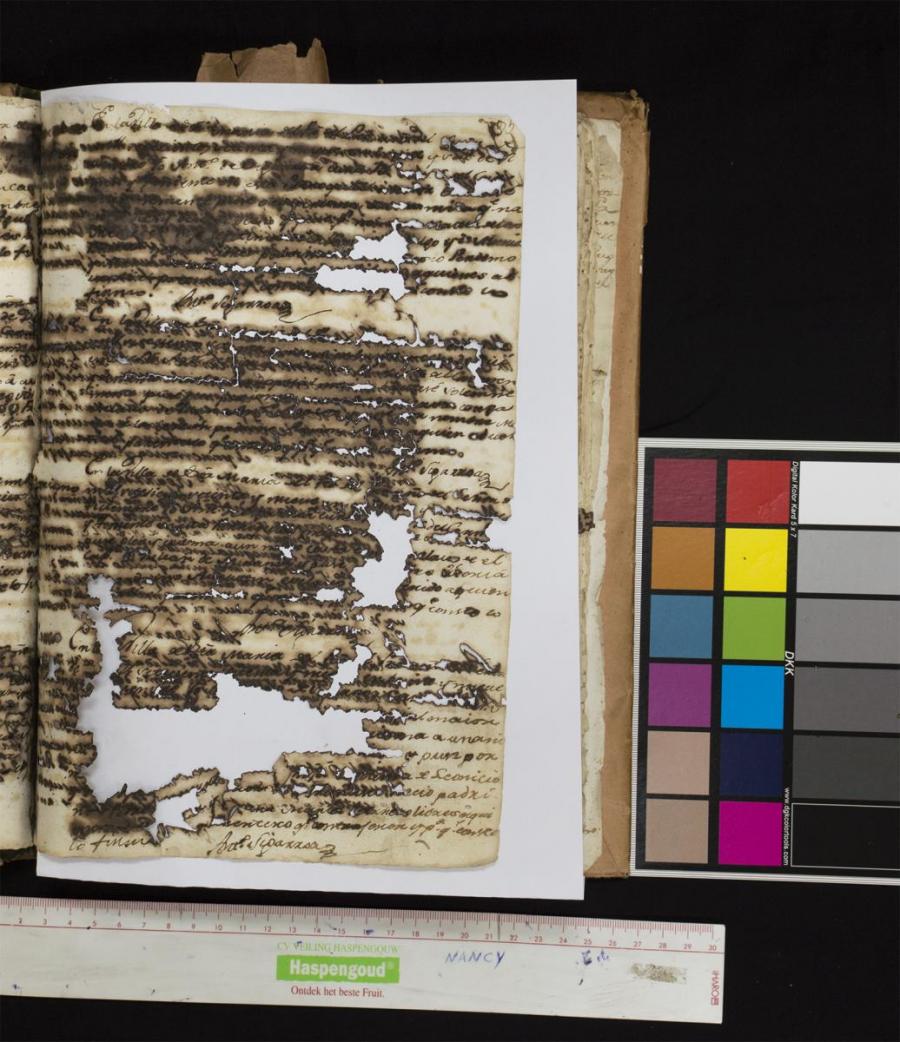

The natural environment has accelerated processes of decomposition among these tomes. Many are too deteriorated to open without doing irreparable damage to them. Mold provides fodder for book-boring insects, while the general humidity and extreme weather, especially in the coastal towns, present other challenges to preservation. Few domestic or international attempts have been made to duplicate, preserve, or even index most of the sources—some of which extend into the sixteenth century, when the transatlantic transfer of biota and ideas set in motion the socio-ecological transitions and feedbacks still reverberating today. During this time the Church was a much more integral part of society; as such, it served as the primary repository for written data on socio-ecological processes. With respect to the volume, depth, and potential resolution of these primary sources, there is no equivalent.

SESYNC postdoctoral fellow Matthew LaFevor and University of Texas (Arlington) history professor David LaFevor, both paleographers, visited the seven ‘original’ towns of Cuba from July 2–16, 2015, on a research trip funded by the British Libraries Endangered Archives Programme (BLEAP). Their purpose was to establish contacts with the clergy from these towns, to identify archival repositories in need of preservation, and to lay the foundations for larger, longer-term digitization projects in collaboration with local people.

With funding from the BLEAP and letters of introduction from Church leadership in Havana, the two researchers began collaborations with clergy from six of the seven original towns: Havana, Baracoa, Bayamo, Santiago de Cuba, Camagüey, and Trinidad. (The seventh town, Sancti Spíritus, was omitted due to time constraints.) Major repositories of archival documents numbering in the hundreds of thousands of pages were identified. The team took photographic indices of these collections and documented the different states of deterioration to determine preservation priorities. They made contacts with sacristans, students, and other potential collaborators and laid the groundwork for future preservation efforts.

The LaFevors, as co-directors of the project, are currently writing a report on their preliminary findings to the BLEAP and drafting a larger proposal to expand work on the project. If funded, local groups would receive instruction on archival preservation, cameras, computers, and other equipment for the purpose of preserving their archives for the Church, for the Cuban people, and for researchers. The Cuba digitization project would serve as an extension of the Vanderbilt University Ecclesiastical & Secular Sources for Slave Societies (ESSSS) project, directed by Jane Landers. The project is currently digitizing endangered documents in Brazil, Colombia, and Spanish Florida.

Photos from top to bottom:

- Ancient archives from Trinidad, Cuba.

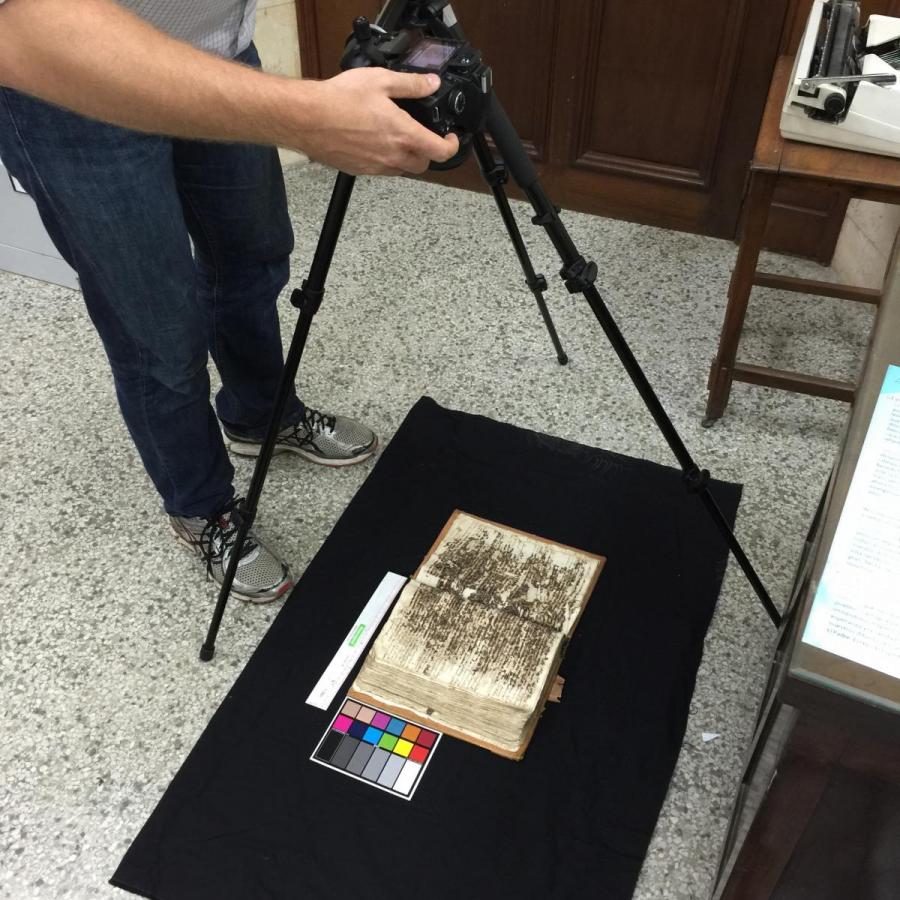

- Collaborating with sacristan in Havana on preservation of archives.

- Building a high-resolution digital registry in Camagüey takes time.

- Data decomposition ends here. Image preserved. Holes will be filled by future researchers.

All photos copyright of Matthew and David LaFevor.

The National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center, funded through an award to the University of Maryland from the National Science Foundation, is a research center dedicated to accelerating scientific discovery at the interface of human and ecological systems. Visit us online at www.sesync.org and follow us on Twitter @SESYNC.